By Michael Corcoran

Published on 2/1/04, the 15th anniversary of Foley’s killing.

The years since his 1989 passing have been kind to Blaze Foley.

While he was alive, the singer-songwriter had released only a single and an LP that was never distributed aside from a box full of vinyl albums he would barter for beers and cab rides.

In recent years, the “derelict in duct tape shoes” of the 1998 Lucinda Williams’ song “Drunken Angel,” has vaulted to folk hero status. Merle Haggard and Lyle Lovett are among those who have recorded his compositions, plus he’s inspired four tribute albums and is the subject of two upcoming films.

His killing at age 39 continues to haunt an Austin music community that has suffered its share of cancer fatalities, drug overdoses, suicides and car wrecks, but has had little experience coping with the shooting death of one who writes songs.

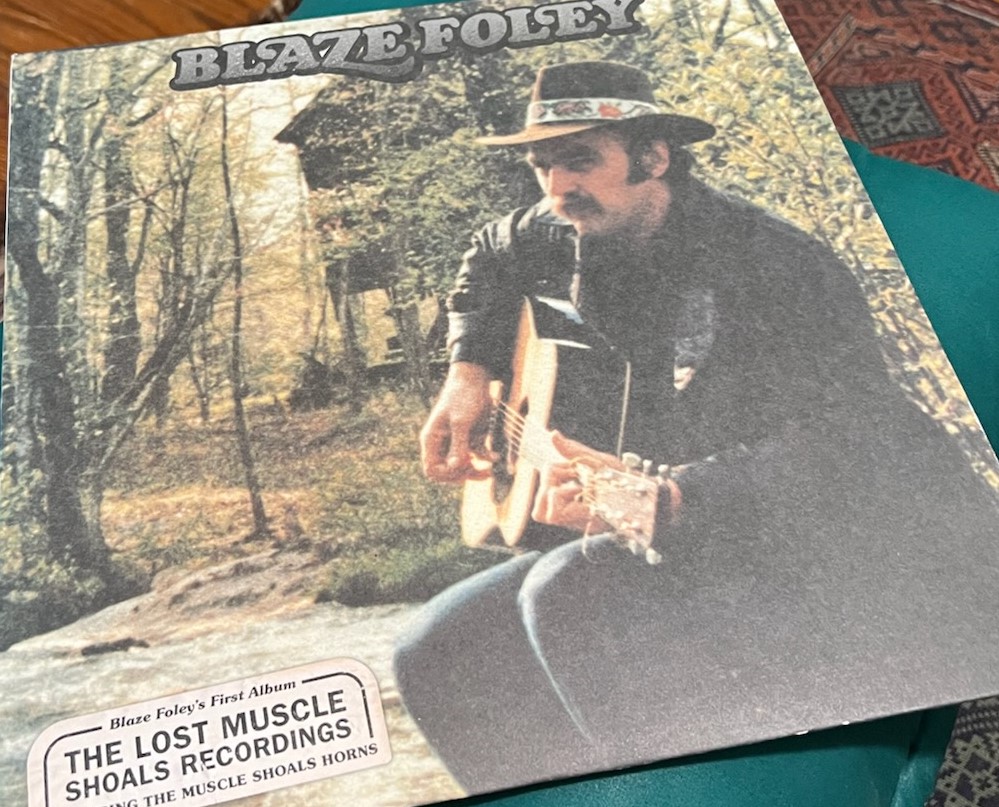

Blaze Foley by C.P. Vaughn

All these years later, his friends and fans still question the jury’s verdict that acquitted Carey January of Foley’s murder by reason of self-defense. Saying he feared for his life, January admitted shooting Foley, a friend of his father, Concho January, with a .22-caliber rifle in the predawn hours of Feb. 1, 1989. The defense portrayed the 6-foot-2, 280-pound Foley as a menacing bully, violently injecting himself into a family dispute.

An ice storm blew into Austin the day of Foley’s funeral. At the jam-packed service, guitarist Mickey White passed out the lyrics to “If I Could Only Fly,” Foley’s trademark song, and as the ragtag congregation sang those words about wanting to soar above human limitations, the song grew spiritual wings. Without the money for a police escort, the funeral procession got smaller with each red light and almost everyone got lost. Cars did doughnuts on the ice and packs of autos tore down South Austin streets in all directions. Many of the mourners didn’t make it to the burial at Live Oak Cemetery.

Someone at the grave site busted out a roll of duct tape, Foley’s favorite fashion accessory, and folks started adorning the casket. Some of his friends made duct tape armbands or placed pieces over their hearts. Kimmie Rhodes started singing an old gospel song when the body was lowered and the tears nearly froze before they hit the ground.

“The whole day was so chaotic, yet so beautiful,” guitarist Gurf Morlix recalled in 2004. “It was exactly the way Blaze would’ve wanted it.”

They always talk about his eyes, how he could fix a glance on you and make you feel either two feet tall or like a million bucks. Those who knew him well — a number that seems to grow every year — use words like compassionate, honest and courageous to describe a lumbering giant whose songs could make hard men cry. But his friends also remember Foley as belligerent, abrasive, highly opinionated and drunk more often than not.

There were two Blaze Foleys, and if you didn’t know both of them you didn’t know either.

Songwriter Mandy Mercier lived with Foley from 1980 to 1982, and while Mercier worked temp office jobs to pay the bills, Foley would stay home with a pack of fellow ne’er-do-wells who passed around guitars and bottles of hooch. Folks would ask Mercier and her roommate Lucinda Williams — who shared a soft spot for self-destructive rogues — what they saw in such men. “They had something that we wanted,” Mercier said. “Creative conviction. They would explore difficult subjects, but they could walk the walk.”

There was a hobo camp near the railroad tracks behind Spellman’s, the former folkie haven on West Fifth Street, and Foley would tell Mercier that if she had any guts, she’d quit her job and live there and write songs all day.

During the times he was without a girlfriend or a friendly couch, he’d sleep wherever — and whenever — he could. Though he preferred flopping on top of pool tables (or below them during hours of operation), he’d sometimes sleep in dumpsters on cold nights. “See that ‘BFI’?” he’d say, pointing to the logo of the waste removal company seen on dumpsters. “That stands for ‘Blaze Foley’s Inside.’”

Foley lived on the edge because that’s where the best stories drift off to. “There’s a scene in the movie Salvador where one of the characters is telling a wartime photographer that the key is to get close enough to the subject to get the truth, but not too close or you’ll get killed,” said Mercier. “That’s how Blaze wrote songs, from the front lines of experience.”

Foley was fearless, all his former associates agree. “Blaze had no doubts about his immortality. He thought he was bulletproof,” said songwriter Carlene (Jones) Neuenschwander, living in Colorado in 2004. “I guess that proved to be his undoing.”

Common sense told Blaze Foley to keep out of a father-and-son relationship that he saw as abusive. After all, Blaze’s friend Tony “Di Roadie” Scarano gave statements to police that they had heard Carey January, a 39-year-old black male known as J.J., threaten to kill Foley if he didn’t stop coming around the house at 706 W. Mary St. in South Austin. But then, common sense didn’t pull much weight with this wild-eyed maverick, who delighted in newspaper headlines like “Blaze Destroys Warehouse.” He was 100-percent songwriter and nothing cool rhymes with logic.

Foley had met 66-year-old Concho January in June ’88. The singer was living two blocks away, on the old man’s route to David’s Food Store, and one afternoon Blaze and a half dozen other songwriters were picking on the porch when Concho stood to listen for a few moments before heading on for a bottle of Thunderbird wine. On the way back, Foley waved the elderly black man inside the gate.

After about an hour Carey showed up and started yelling at Concho to get home. “Blaze didn’t like the way J.J. was talking to the old man,” says Neuenschwander, one of the pickers. Foley started dropping in on Concho and the two became drinking buddies. If Foley could borrow a car, he’d take Concho on errands, including cashing his Social Security check the first of the month. Stories about “my old pal, Concho” started creeping into Foley’s between-song chatter.

“That was just like Blaze to latch on to some poor, old, lonely man who’d been through some rough times,” says musician Lost John Casner.

The teeth-baring acrimony grew between Foley and Carey January, an ex-con who had spent four years in prison for a 1975 charge of heroin delivery. It escalated into violence on Aug. 9, 1988.

Police received a disturbance call at 706 W. Mary St. that afternoon and found Foley and a neighbor sitting on the steps holding ax handles with black electrical tape for grips. Carey was across the street, yelling to the cops that those men beat him with the clubs. Foley admitted hitting Carey across the back and on the head, but said he was just defending Concho from the latest beating at the hands of his son. The police report described Foley as “very intoxicated.”

Foley pleaded nolo contendre to unlawful possession of a weapon and received 180-days probation and a court order to attend at least two Alcoholics Anonymous meetings a week.

Friends say that the singer managed to stay sober for a couple weeks at a time but then would fall off the wagon hard, going on drinking binges.

Foley seemed to have been on a tear the last night of his life. Early in the evening, he was 86-ed from the Austin Outhouse when he got in the face of a regular who had used an anti-Arab slur while watching the 6 o’clock news.

The next stop was the Hole In the Wall, which had recently lifted a longtime Blaze ban at the behest of Timbuk 3, who were at the height of their “Future’s So Bright I Gotta Wear Shades” phase. The duo of Pat MacDonald and Barbara K didn’t forget that Foley was their first Austin friend and supporter. It didn’t take long for Blaze, who always seemed to be ranting about something, to be shown the door at the Hole.

He ended up at the South Austin home of fellow hard-living songwriter Jubal Clark, then borrowed a friend’s Suburban, without permission, to drop in on Concho at about 5 in the morning. The old man had a lady friend over and the three drank cheap wine until Carey emerged from his bedroom and a single gunshot broke up the party. Foley was shot at about 5:30 a.m. He was pronounced dead at Brackenridge at 8:14 a.m.

“I got home from a gig late one night and there was a phone message from Lucinda (Williams),” Morlix recalled. “She said there was something she had to tell me but that she’d call me back in the morning. I just sat down and cried. I knew it was Blaze. I knew something bad had happened.”

Defendant Carey January talked about Foley’s eyes when he took the stand in September 1989 to claim that he shot the songwriter out of fear for his life. “He was coming at me,” January testified. “I could see fire in his eyes. … I had seen that look before, when he hit me with the ax handle.”

When police arrived at 706 Mary St. minutes after the shooting, Foley was outside, lying face down on the ground, clutching a blue notebook. When they asked him what happened, Carey January said, “I don’t know.” Foley, still conscious but bleeding badly, was able to answer. “He shot me.” Who? the officer asked. “The guy you’re talking to,” said Foley.

Concho January told police that Carey killed Foley without provocation, as the songwriter was sitting in a bedside chair, showing the old man a book of his drawings.

Twelve days after the killing, someone set Concho’s house on fire while he slept. Though the arsonist was never found, the police report noted that Concho was a state’s witness against Carey, who was in jail. But Concho, who died in 1994 at age 71, was not intimidated. He testified at the trial that Carey shot Foley in cold blood. The elder January, whom defense attorneys dismissed as “an old fool” and “the world’s most reliable drunk,” proved to be ineffective.

“You don’t choose your eyewitnesses. That’s the risk of every prosecution,” says attorney Kent Anschutz, who still pains over losing the case when he was assistant district attorney. “But I have to tell you that my heart sank when Concho got up on the stand and couldn’t even point out his son right in front of him.”

The jury deliberated just over two hours before finding Carey January not guilty of first-degree murder by reason of self-defense.

The release party for the essential Live At the Austin Outhouse cassette, recorded a month before Foley died and featuring such signature Blaze tunes as “Clay Pigeons,” “Small Town Hero,” “If I Could Only Fly” and “Election Day,” was intended to be a benefit for a local organization for the homeless. Instead, proceeds went to cover the balance due on Foley’s funeral costs.

It seemed, at the time, that the cassette would be the last anyone heard of Blaze Foley, but friends, including singer-songwriters Rich Minus, Calvin Russell and Pat Mears, have done much to keep Foley’s songs alive, recording three albums of Blaze covers and one album of odes to the songwriter. Live At the Austin Outhouse, released on CD in 2000, has become a cult favorite, especially in Europe.

It doesn’t hurt that the songwriter’s biggest fan was country music’s greatest living legend (until 2016). “Merle Haggard’s obsessed,” said Mercier, who like several former Foley associates had been summoned to Haggard’s bus. “He wanted to know about Blaze’s life experiences. I told him that Blaze had had polio as a child, so one leg was shorter than the other and he’d sorta drag his foot when he walked. Merle was so moved by that image.”

Michael David Fuller, who was born in Malvern, Arkansas, performed his first set as “Blaze Foley” in 1977 at Austin dance club Valentine’s, behind the Hole In the Wall, which booked singer-songwriters during happy hour. “He was hilarious and his songs were great,” said Morlix, one of six audience members. “He’d pull stuff out of his bag and give a little show-and-tell presentation between songs.”

For the next three years Foley and Morlix were inseparable, moving to Houston and inhaling the fragrant Montrose folk scene, where Shake Russell, John Vandiver, Nanci Griffith and Townes Van Zandt were regulars.

Blaze 1983. Photo courtesy Marsha Weldon.

Foley had started writing songs in Georgia in 1975, where he billed himself “Dep’ty Dawg” and tried not to sound too much like his model John Prine. But he truly came into his own in Houston. “There were better singers, better songwriters, but no one was more committed to his songs than Blaze,” Morlix said.

It was inevitable that he and Van Zandt would become hard-drinking runnin’ buddies. “Blaze idolized Townes — not only his songs, but his lifestyle. He started drinking vodka, Townes’ drink,” said Morlix. “Sometimes it got out of hand.”

Of Foley, whom he immortalized with 1994’s “Blaze’s Blues,” Van Zandt used to say, “Blaze has only gone crazy once. Decided to stay.”

Van Zandt, who passed away the first day of 1997, credited Foley with inspiring “Marie,” his bleak masterpiece. “Blaze was real interested in the dispossessed,” Van Zandt told KUT radio’s Larry Monroe in 1991. “I thought a lot about Blaze when I wrote ‘Marie’ because he had so much to do with turning me on to that problem.”

Morlix recalled that whenever Foley raged — and it was often — the subject was almost always some sort of injustice, real or perceived. But sometimes his unwillingness to back down from any confrontation was just plain scary. Once in Los Angeles, when Foley was talking to a topless dancer outside on her break, her jealous boyfriend pulled a gun and said to get lost. “Blaze said, ‘Just go ahead and shoot me,’” said Morlix, a stunned witness. “I’d bet Blaze said the same thing to the guy in Austin.”

At the 35th reunion of the old L.C. Anderson High School class of ’68 in 2003, one former student brought framed certificates to the Hilton gathering. But, then, perhaps Carey January felt he had a lot more to prove than his classmates, who passed around wallet-sized photos and business cards.

“We were all so happy to see J.J.,” said fellow alumnus William Ward. “Everybody knew about that problem he had with the shooting, so it was so good to know that he had turned his life around.” Ward said he spent a long time talking to January about how life is just a series of choices and all you have to do is make the right ones.

“How did you get my number?” asked a 54-year-old January in 2004. He had lived for 10 years in Los Angeles, where he says he is an outreach specialist. He says he’s received several citations, including one from then-Gov. Gray Davis commending his efforts to get health insurance for the underprivileged. He strongly declined to comment on any aspect of the Foley murder case.

“It was 15 years ago,” he said. “I was acquitted. I’ve moved on with my life. I’m not O.J. Simpson. I don’t want any publicity.”

Sometimes in death you get what you deserved in life. Foley always wanted to be considered a great writer, not just a good one, mentioned alongside his heroes Prine, Haggard and Van Zandt. In 2005, Prine covered Foley’s “Clay Pigeons,” to make the circle complete.

All these years after he died clutching a notebook outside 706 W. Mary St. on Feb. 1. 1989, Blaze Foley’s legacy is as rich as he could’ve hoped for. Like the homemade trinkets and little Goodwill toys he would slide into the hands of friends, his songs are the humble, well-worn gifts he left behind.