Rhyolite ghost Town history from the national Park Service

In 1904, prospectors Frank “Shorty” Harris and Ernest “Ed” Cross were exploring the desert hills on Nevada’s western border when they discovered high-grade gold ore. They named their claim Bullfrog — after the area’s green-hued rocks — and within a year, several mining camps were set up nearby, adding to what became known as the Bullfrog Mining District.

Word of this wildly lucrative operation spread all the way north to Goldfield and Tonopah, and people began arriving by the thousands. During this rush, four daily stagecoaches connected Goldfield to the Bullfrog Mining District, ushering in a steady flow of people to Nevada’s newest gold discovery. In 1905, the town of Rhyolite was founded in the heart of the Bullfrog Mining District. What started as a two-tent mining camp boomed into a bustling town of around 5,000 people within six months. While mining camps such as the Montgomery-Shoshone Mine were very common in Nevada during the late 1800s and early 1900s, Rhyolite stood out for its valuable ore samples.

As if Rhyolite sprung to life overnight, this community quickly became the epicenter of the Bullfrog Mining District and aside from a swelling population boasted…

- 50 saloons

- 35 gambling tables

- 19 lodging houses

- 16 restaurants

- several barbers

- a public bath house

- a red light district

…and the Rhyolite Herald—a weekly newspaper publication. To add to an already growing population, a hard-to-imagine four daily stagecoaches connected “The World’s Greatest Gold Camp” to Rhyolite, ushering in a steady flow of people to Nevada’s newest gold discovery.

Rhyolite was so successful that it soon caught the attention of steel magnate and savvy businessman Charles M. Schwab. In 1906, Schwab purchased the Bullfrog Mining District, which elevated the operation from good to grand. With Schwab’s leadership, Rhyolite secured a contract with the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad, and within a year, three railroads were connected to Rhyolite’s brand-new — and still perfectly preserved — train station.

Also thanks to Schwab, Rhyolite residents enjoyed luxuries not usually associated with mining boomtowns like concrete sidewalks, telephone lines, electric street lamps, and plumbing, Downtown’s commercial buildings —many built from stone—included a hospital, three banks, a stock exchange, an opera house, a public swimming pool, and two churches.

While Rhyolite and the Bullfrog Mining District produced more than $1 million within three short years — about $27 million by today’s standards — this boomtown declined almost as rapidly as it came to life. Like most other has-been mining communities, the high-grade ore began to diminish, and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake proved to be the kiss of death as the rail service was seriously disrupted.

By 1910, mines began to close, businesses failed, and workers sought employment elsewhere. By 1914, the city lost electricity, and the banks, newspapers, post office, and train depot all closed. In1920, only 14 people called Rhyolite home.

Because timber and stone were rare resources in the desert, most of Rhyolite’s infrastructure and buildings were taken apart to be used elsewhere. In nearby Beatty, material was recycled to make new buildings, including the schoolhouse. Sometimes entire buildings were moved, like The Miners Union Hall, which is now the Old Town Hall in Beatty. In 1913, one of Rhyolite’s original saloon bar tops was relocated to Goodsprings, where it is still a fixture in the Pioneer Saloon.

The area is coming alive again! This time the rush is for lithium to make batteries. Let’s keep an eye out for increased ghost activity.

This information is from the Ioneer website

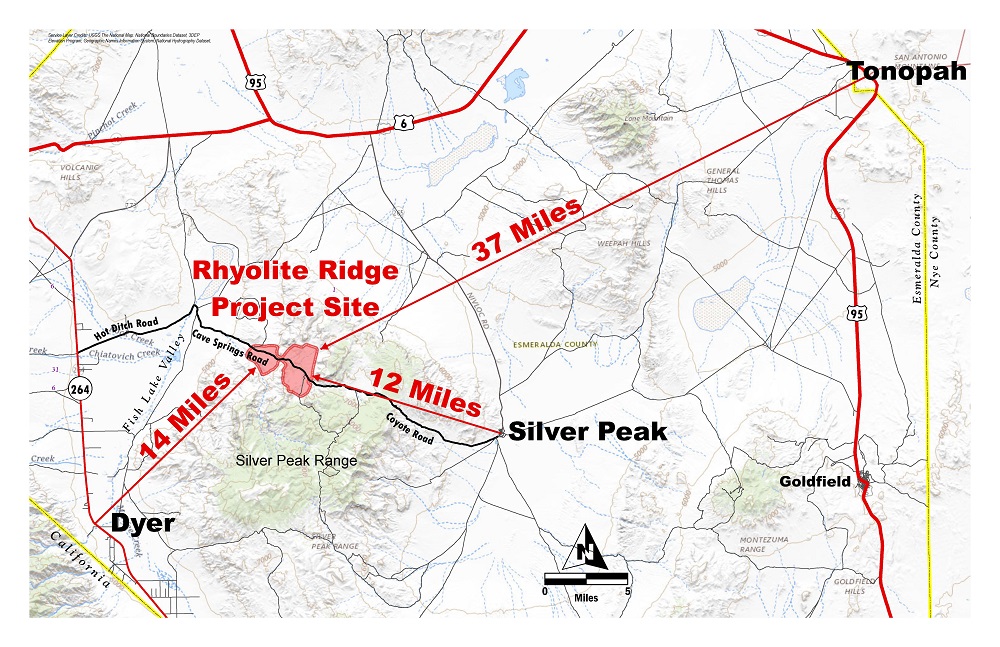

The Rhyolite Ridge Project site is situated in the Silver Peak Range, part of the larger geo-physiographic Basin and Range Province of western Nevada. Horst and graben normal faulting is the dominant characteristic of the Basin and Range Province, which is believed to have occurred in conjunction with large-scale deformation due to lateral shear stress. This is evidenced in the disruption of large-scale topographic features throughout the area. The project area sits within the Walker Lane Fault System, a northwest trending belt of right-lateral strike slip faults.

Rhyolite Ridge is a geologically unique lithium-boron deposit that occurs within lacustrine sedimentary rocks of the South Basin, peripheral to the Silver Peak Caldera. The South Basin within the project boundaries measures 4 miles by 1 mile and covers an area of just under 2,000 acres.

The regional geology is characterized by relatively young Tertiary volcanic rocks thought to be extruded from the Silver Peak Caldera, which date to approximately 6.1 million to 4.8 million years old. The northern edge of the Silver Peak Caldera is exposed approximately 2 miles to the south of the South Basin area and is roughly 4 miles by 8 miles in size. The Tertiary rocks are characterized by a series of interlayered sedimentary and volcanic rocks, which were deposited throughout west-central Nevada. These rocks unconformably overlie folded and faulted metasedimentary basement rocks that range from the Precambrian through Paleozoic periods.